By Dr Natalie F. Mylonas |

| "This Bulletin, unlike others in this series, has been made the vehicle for contentious theory of a kind which belongs to early and eclectic research, not to the historian’s considered verdict." |

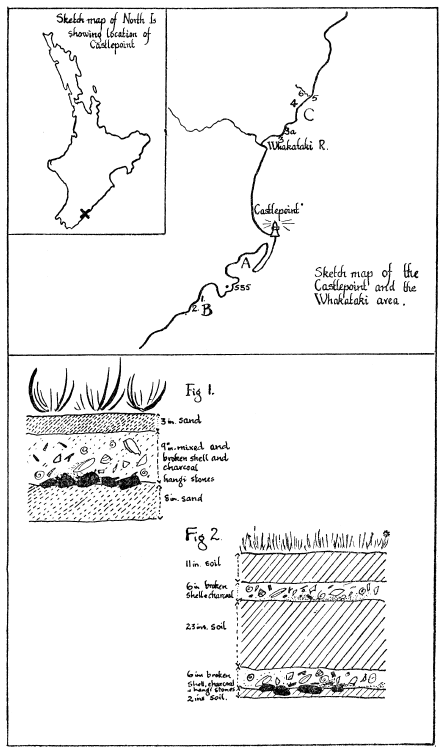

| It is interestingly supplemented by the archaeological notes of Susan Davis, notes which contain information about the site both before and after the existence of the barracks. It is a matter for conjecture whether the interests of the Trust would have been better served if Susan Davis's notes, published elsewhere, had formed the basis for this Bulletin rather than the insecure argument of Mr Burnett's 'fustian grenadiers' versus the 'bubble-gum’ of Dr Miller's 'unimaginative British soldier '. We might then have known more about the defended site of the whaling days, and of the shearing shed of a later era, without being involved in hypotheses of doubtful relevance. |

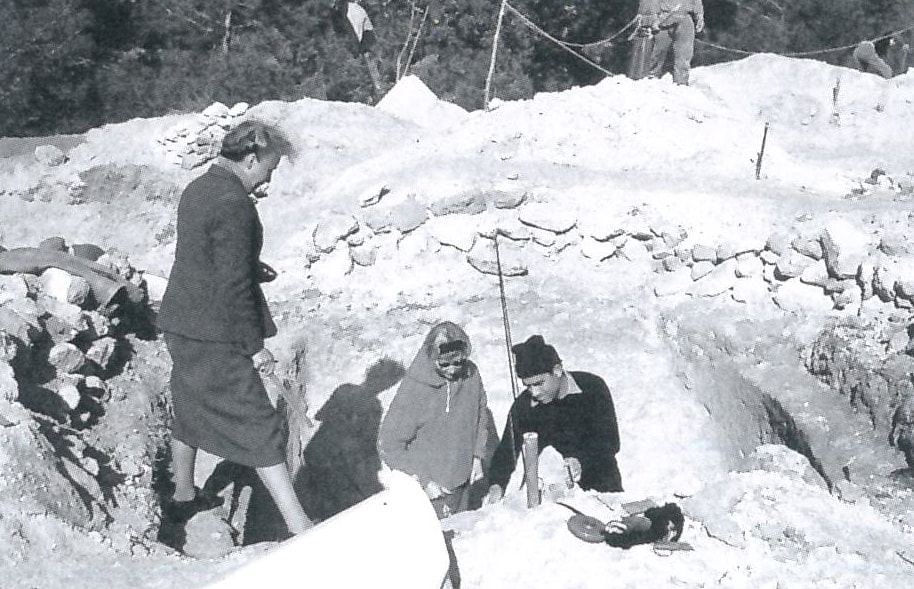

From 1956 to 1960, Susanna appears in several newspaper articles for The Evening Post. One such article contains a striking image of herself and the secretary of the Historic Places Trust, Mr John Pascoe, at the aforementioned Paremata Barracks (Figure 4). One can just make out the trowel in Susanna’s hand by her side. There is something to be said here about archaeology in reality vs imagined archaeology and its presentation to the general public. This particular scene was constructed for photographic purposes and Susanna played a crucial role, at a critical time period, in normalising the place of women in the field and subverting public perceptions.

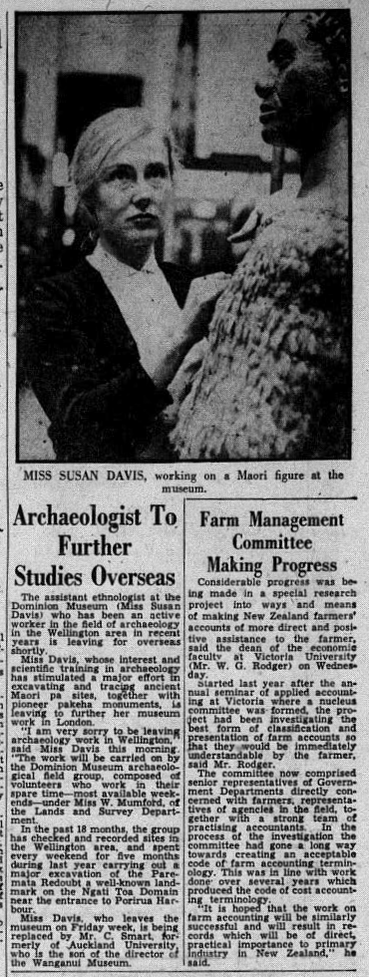

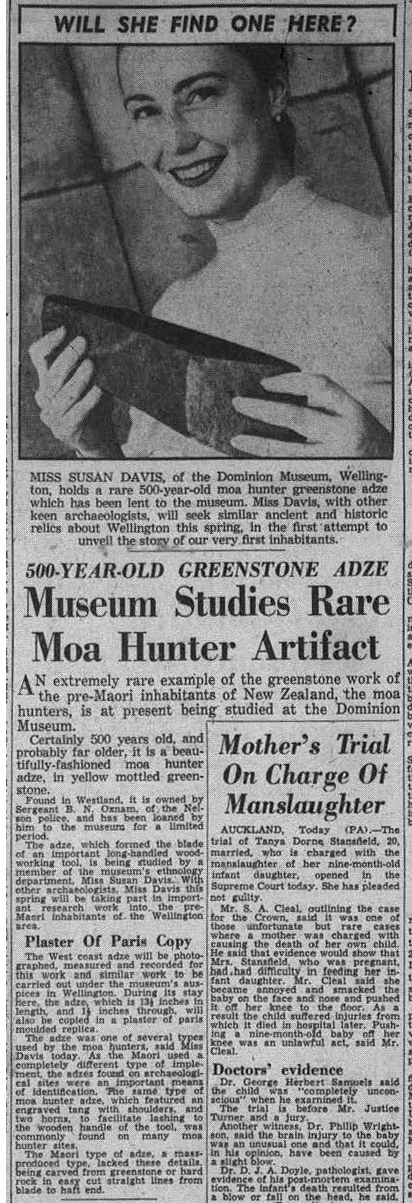

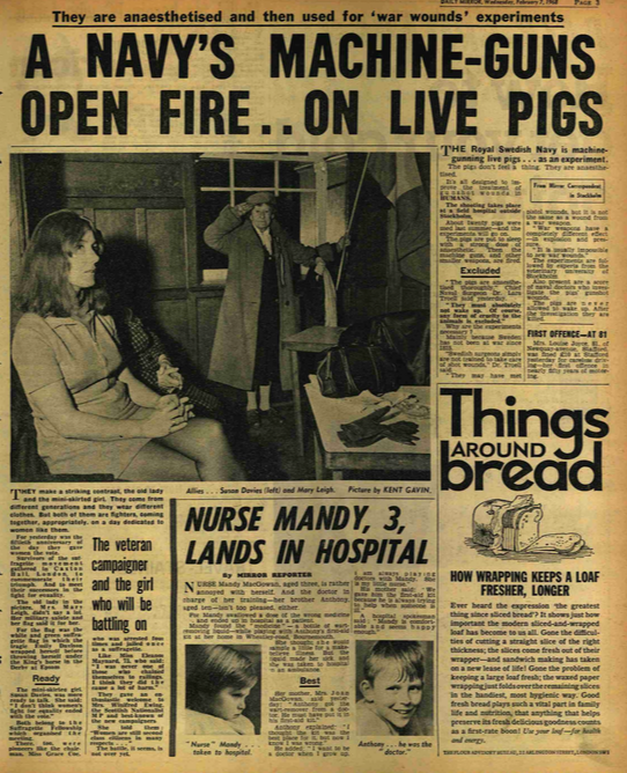

Figure 5. The Evening Post article, 29th April 1960, p. 18

Figure 5. The Evening Post article, 29th April 1960, p. 18 In mid-1963, Susanna left the SWM to take a curatorial position at Guildhall Museum. She then moved to London Museum where she curated exhibitions drawing on the museum’s collections of historic jigsaws and the suffragist movement. During this time, she joined the Suffragettes Fellowship, lending her voice to advocate for women’s rights (Figure 6).

Leaving the London Museum in 1968, Susanna travelled to the USA to work on Plimoth Plantation, Massachusetts, where she took part in the famous re-creation of the 17th century settlement founded by the Pilgrim Fathers. Her work involved researching and commissioning accurate copies of appropriate period furniture and soft furnishings, as well as correct costume for the living history interpreters in the houses.

After her second return to the UK, Susanna held curatorial positions at a number of well-known museums, Bewdley Museum in Worcestershire (1974 to 1982), Cider Museum in Heresford (1982 to 1985), and Ayscoughfee Hall at Spalding, Lincolnshire (1985 to 1995), before retiring in 1995 to Wales where she resides today.

Our research shows that after moving back to the UK from NZ, Susanna’s publication output decreases, which is reflective of her shift in focus from archaeological sciences and research to an alternative career pathway focussing in museums. While Susanna’s time as a professional archaeologist in NZ might be considered brief, there is no doubt of the lasting impact her research has had in the development of the archaeological discipline in the Pacific region.

Acknowledgements

References

- Anon. 1957 500-year-old greenstone adze. Museum studies rare moa hunter artifact. The Evening Post, 8th August 1957, p. 12.

- Anon. 1960 Archaeologist to further studies overseas. The Evening Post, 29th April 1960, p. 18.

- Anon. 1968 The veteran campaigner and the girl who will be battling on. Daily Mirror, 7th February 1968, p. 3.

- Burnett, R.I.M. 1963 The Paremata Barracks. Wellington: Govt. Print. in conjunction with the National Historic Places Trust.

- Cranstone, B.A.L. 1963 A unique Tahitian figure. The British Museum Quarterly 27(1/2): 45–48. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/4422812)

- Davidson, J.M. 2019 The Cook Voyages Encounters: The Cook Voyages Collections of Te Papa. Wellington: Te Papa Press.

- Davis, S. 1957 Evidence of Maori occupation in the Castlepoint area. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 66(2): 199–203. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/20703605)

- Davis, S. 1959 A summary of field archaeology from the Dominion Museum Group. New Zealand Archaeological Association Newsletter 2: 15–19. (https://nzarchaeology.org/download/a-summary-of-field-archaeology-from-the-dominion-museum-group)

- Davis, S. 1962 Interim report: Makara Beach (Wellington) excavation. New Zealand Archaeological Association Newsletter 5: 145–150. (https://nzarchaeology.org/download/interim-report-makara-beach-welington-excavation)

- Davis, S. 1963 A note on the excavations of the barracks at Paremata. In R.I.M. Burnett (ed.), The Paremata Barracks, pp. 25–29. Wellington: Govt. Print. in conjunction with the National Historic Places Trust.

- Dreaver, A. 1997 An Eye for Country: The Life and Work of Leslie Adkin. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

- Duff, R. 1960 New Zealand. Asian Perspectives 4(1/2): 111–117. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/42927491)

- Leach, H.M. 1976 Horticulture in prehistoric New Zealand: an investigation of the function of the stone walls of Palliser Bay. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin.

- Leach, B.F. 1976 Prehistoric communities in Palliser Bay, New Zealand. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin.

- Leach, B.F. and H.M. Leach (eds) 1979 Prehistoric Man in Palliser Bay. Wellington: National Museum of New Zealand.

- Prickett, N. 2004 The NZAA—A short history. Archaeology in New Zealand 47(4): 4–26. (https://nzarchaeology.org/download/the-nzaa-a-short-history )

- Wards, I.M. 1963 The Paremata Barracks by R.I.M. Burnett. Political Science 15(2): 82–85. (https://doi.org/10.1177/003231876301500222)

Written by David Frankel

Emeritus Professor of Archaeology, La Trobe University

Originally postedAAIA blog, March 2021

From these initial classes through to post-graduate study Judy introduced me and my fellow students to the masochistic joys of research, of continual questioning and of all facets of archaeology, and always with her characteristic energetic engagement with ideas. This included early exposure to the developing challenges of the New Archaeology in the late 1960s: challenges at odds with the very traditional approaches of other archaeologists, especially some in her own department. But theory had to be matched by practice, for Judy saw that it was essential for students to gain experience in the field in order not only to develop skills, but also to understand the nature of the archaeological record and its potential, even if this had to be done against departmental policy.

Of course the multiple demands of excavation are not for everyone, but from my first exposure I found them both exciting and challenging. I was fortunate enough to spend many months of 1967 working with archaeologists of the calibre of Jack Golson (in New Zealand) and Ron Lampert (at Burrill Lake in NSW) and on several sites in Israel.

The value of this experience became evident in the Sydney University expedition to Zagora in Greece, as there was a cohort of students well equipped for the work. This project had been designed to take advantage of the varied interests and abilities of the Archaeology staff. Judy was naturally entrusted to manage the fieldwork, where she set up the general frameworks and strategies which continued after she was no longer involved.

Editorial note

Written by Emily Simons and Madaline Harris-Schober

University of Melbourne

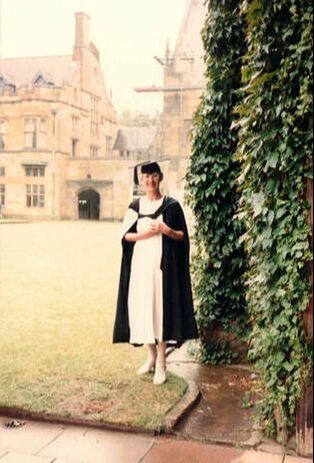

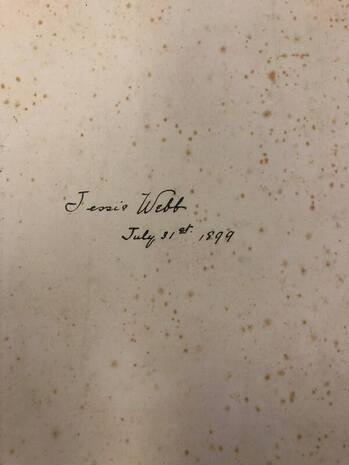

Jessie Webb in academic dress, University of Melbourne. 1975.0048.00007

Jessie Webb in academic dress, University of Melbourne. 1975.0048.00007 Webb was born on 31 July 1880 near Tumut, New South Wales, with her mother passing shortly after and her father dying in an accident when she was nine years old. She then moved with her aunt, Jean Lauder Watson, to Melbourne where she lived for the rest of her life. Jessie was among the second generation of women to graduate from the University of Melbourne, and she continued working there for the rest of her life. She joined the staff at the University of Melbourne in 1908, becoming a senior lecturer in 1923. She functioned as acting professor three times before her death in 1944.

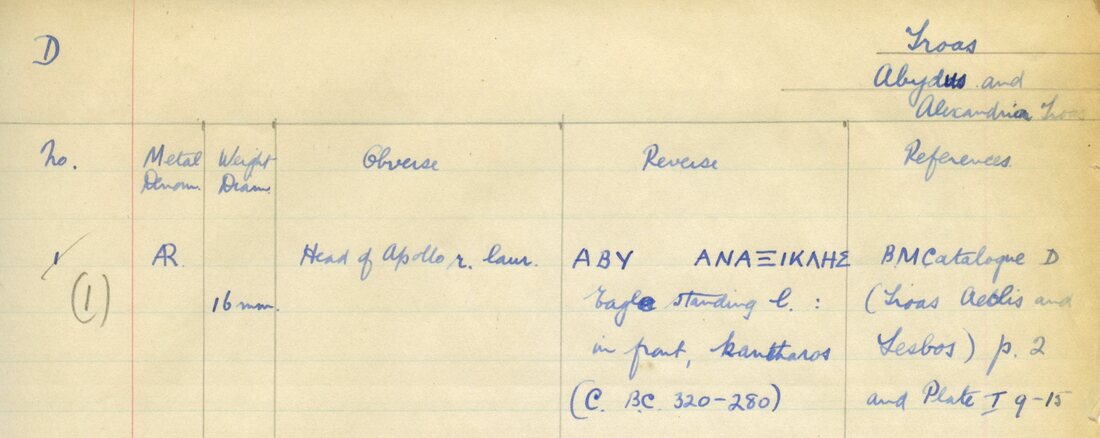

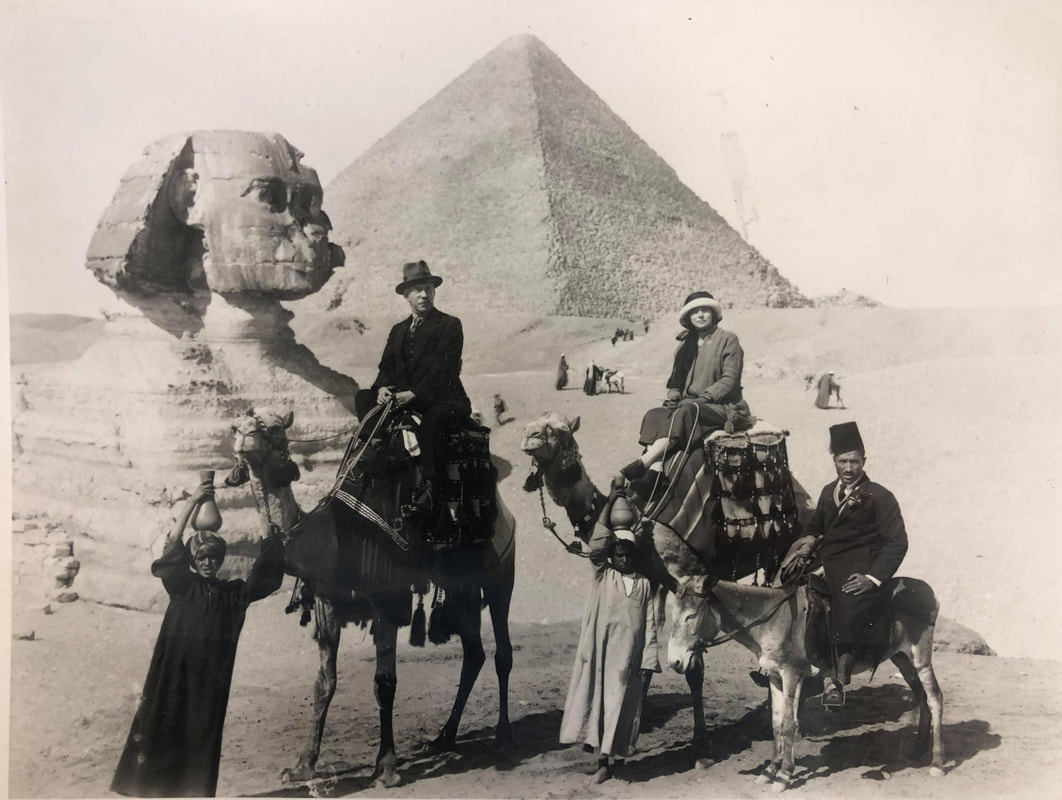

Throughout her time at the University, Jessie had an enormous impact on developing the Classics and Archaeology Collection at the University. While teaching at the University of Melbourne, Jessie made two research trips abroad, travelling through Africa to Europe and the eastern Mediterranean; she explored sites that she had spent a lifetime teaching, places that inspired her. These visits 1922–1923, and then again in 1936, proved a catalyst for building the teaching collection and provided a significant amount of story-telling material for students and public lectures. After her first trip, she persuaded the University to contribute 20 to 25 pounds a year to purchase 'representative Greek and Roman coins' to become part of a teaching collection. The collection now comprises 745 coins.

| My name is Webb, in me you see How much in little there can be, My mind enquiring is in tone, And all its sparkles are my own! Ridley 1994, 39 |

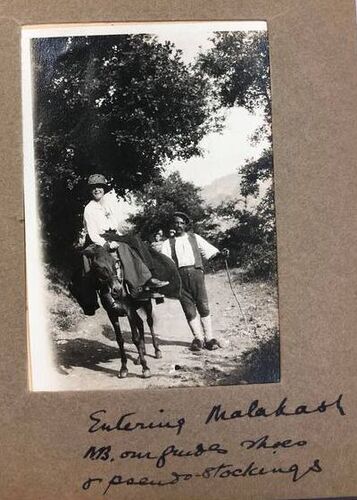

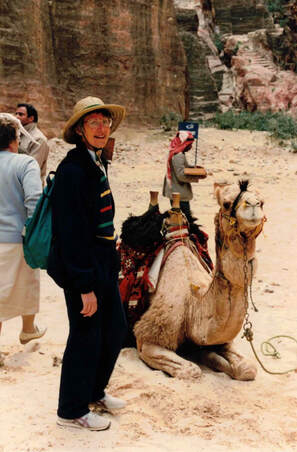

Jessie on a mule during her trip to Greece and Turkey (1922-1923). University of Melbourne Archives 2011.0033

Jessie on a mule during her trip to Greece and Turkey (1922-1923). University of Melbourne Archives 2011.0033 After seven months of rail and ferry travel, Jessie went on to Greece. Jessie spent her leave at the prestigious British School of Archaeology in Athens, travelling to Crete from the mainland to further her research. While there, she met Arthur Evans, and later students recall her stories about him as "Screamingly funny!" (Ridley 1994, 165). At the end of this trip, she was nominated as the alternate delegate to the League of Nations assembly in Geneva where she discovered the plight of Armenian genocide survivors, returning to Australia to raise funds to support refugees.

Upon returning to Australia and subsequent 'lady of the hour' public lectures, Jessie highlighted the need for more female archaeologists and often commented on women's different statuses in different countries and universities. Her recommendation to both Australian and international counterparts was the promotion of mentorship; for educated women to watch for talented students within their fields and to give them all possible help. Jessie was a firm proponent of humanism and was noted for her support of disadvantaged students and women abroad.

Jessie was a trailblazer. Her travels, which now read like an adventure novel to archaeologists and historians alike, portray her as a figure of intellectual vigour, and a woman of understated wit.

It is remarkable that upon her death she bequeathed £7128 to the University of Melbourne to endorse the study of ancient history and archaeology. The fund, originally intended to support her retirement, instead encourages students to spend a 'season' devoted to research in Greece. Jessie created this scholarship from her retirement funds to "assist a student to have the chance she herself never did, to study at the European institution she knew and remembered best, the BSA or equivalent" (Ridley 1994, 141). This remarkable opportunity has benefitted many students in their postgraduate study at the University of Melbourne. Such generosity made Jessie a fantastic teacher and endeared many to her during her time at the University.

It is a humbling experience to write about Jessie Webb and her life for AWAWS and even more so to chronicle some of her adventures and highlight her legacy.

References and further resources

|

Editorial note

Pacific Matildas: Adèle de Dombasle as a pioneer traveler-artist for archaeological illustration

8/2/2021

Written by Emilie Dotte-Sarout

The University of Western Australia

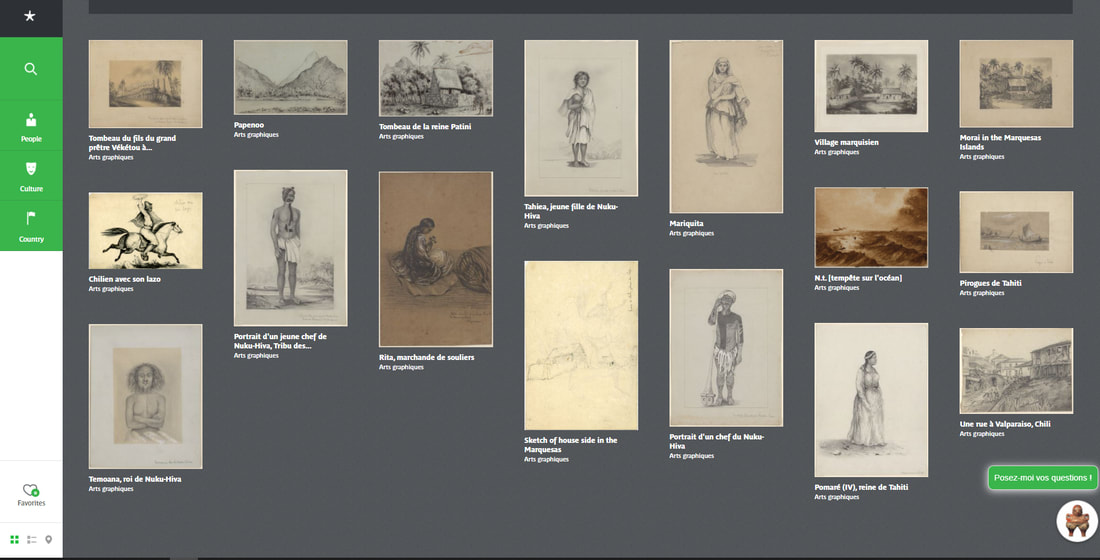

A selection of works by Adèle de Dombasle avalaible from Musée du quai Branly onbline collection http://www.quaibranly.fr/en/explore-collections

A selection of works by Adèle de Dombasle avalaible from Musée du quai Branly onbline collection http://www.quaibranly.fr/en/explore-collections “Do you actually not want to understand, Sir, how much interest I find in seeing the savages truly in their own interiors, in the midst of their customs, surrounded by all the objects they use. I can be told all kinds of long stories about their ways of life, I will only imperfectly learn what I really want to know. The simple inspection of a house will tell me much more. Better than descriptions, it will reveal to me the intimate particularities of their existence. You know it, I came to Noukouhiva with the unique aim of seeing” (De Dombasle 1851: 507).

‘Seeing’ was only the first step in fulfilling her aim though. Indeed, Adèle de Dombasle [2] embarked on this voyage as the “illustrator” accompanying amateur ethnologist Edmond Ginoux de La Coche, who had managed to be entrusted with a mission to Oceania and Chilie for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (de la Grandville 2001). Yet, the mission was cut short after just one week in the Marquesas and three weeks in Tahiti, where Ginoux’s outspoken liberal opinions had made him a few powerful enemies. Clearly, the presence of a woman separated from her husband as the ethnologist’s travel companion provided an additional excuse for condemnation. The local government council issued a specific deportation order against Ginoux that stated he was “a dangerous person and had demonstrated since his arrival in Tahiti a conduct contrary to the good order and tranquility of the colony” (the Governor even visited their hotel to make sure that Ginoux and Ms de Dombasle did not share the same bedroom!) (de la Grandville 2001: 374-377).

Still, Adèle de Dombasle managed to produce several drawings during her travel in Polynesia (and Chile). These represented monuments and sites from the Marquesas, and Tahitian and Marquesan inhabitants with elements of material culture, landscapes and portraits. The details are exceptional (i.e. plant species are identifiable thanks to the precise representations of the leaves and general forms, motifs of tattoos or artefact decorations are finely depicted) and mean that the limited number of her drawings that have been preserved in public collections are a unique source of information for archaeologists working in the region. Unfortunately, only a handful of her illustrations are known and available today: the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris holds 17 of these, while it appears that some of her drawings are still in private family archives (as illustrated in de la Grandville 2001) and others could have been scattered or misattributed after her return voyage to France.

Indeed, according to Ginoux’s biographer, Frédéric de la Grandville, archival sources indicate that the Governor “left Adèle de Dombasle the choice to either stay by herself on the island or accompany Ginoux back”, but they do not record any traces of her decision (2001: 24). Ginoux’s sources describing his long and complicated return trip through the Americas do not mention her, so it appears possible that she took a separate, shorter route (via the Cape Horn and Brazil) back to France. In any case, she was in her home country in 1851, when she published a paper on her experiences in the Marquesas, evoking her delighted discovery of Marquesan landscapes and sites, the context for the tracing of some of her drawings, her attentive encounters with the Marquesan people and their culture as well as her playful and trustful relation with Ginoux. This is a rare document as the only direct source about her experience in Oceania, which clearly shows her curiosity and will to carefully document all her observations, as in this instance when she stops along the track: “I did not want to move away before having augmented my album with a sketch of this picturesque place” (1851: 516).

A further passage records another unclear and potentially important aspect of her anthropological contributions: her role in the making of Ginoux de la Coche’s rich collection of Pacific artefacts, hosted today by the Musée de la Castre in Cannes, southern France. Indeed, de Dombasle narrates how, when she was visiting “the great priestess Hina”, both women entered into a haʼa ikoa (exchange of name involving the formal establishment of kinship relationship). The author recounts how this relationship was sealed through the gift she was offered by the high-ranked woman, bringing

“a necklace, a kind of amulet, made up of a small sperm-whale tooth slipped through a braided bark string, which she came to bind around my neck, asking for my name:

The assimilation of this object offered to Adèle de Dombasle into the ethnographic collection of her male travel companion is striking, especially since a number of pieces of information reveal that she played an essential role in its curation. Notably, she appears to have been the legal heir of the collection after Ginoux’s premature death in 1870, also taking care of his house and library in Nice, eventually making sure that the collection remained intact and properly cared for. A local newspaper article published in 1874 talks about the collection as being “the property of Madam G. de Dombasle” when it was sold to the curator of the Museum of the Baron Lycklama in Cannes, the foundation for the Musée de la Castre (de la Grandville 2001: 387).

Clearly, Adèle de Dombasle’s contributions to the early history of Pacific archaeology deserve a detailed analysis and her life needs to be better documented, an aim that the Pacific Matildas team and colleagues are actively pursuing!

References

- de Dombasle, Adèle. 1851. Promenade à Noukouhiva. Visite à la Grande Prêtresse. La Politique Nouvelle, vol. 3.

- de la Grandville, Frédéric. 2001. Edmond de Ginoux. Ethnologue en Polynésie Française dans les années 1840. Paris: l’Harmattan.

- Dotte-Sarout E. In press. Pacific Matildas: finding the women in the history of Pacific archaeology, Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, https://www.archaeologybulletin.org/collections/special/histories-of-asia-pacific-archaeologies/

- Niku-Hiva, in the Marquesas Islands archipelago of French Polynesia.

- During my research, I have identified “Adèle de Dombasle” as Gabrielle Adélaide Garreau née Mathieu de Dombasle, born 1819-deceased after 1870.

Written by James Donaldson

The University of Queensland

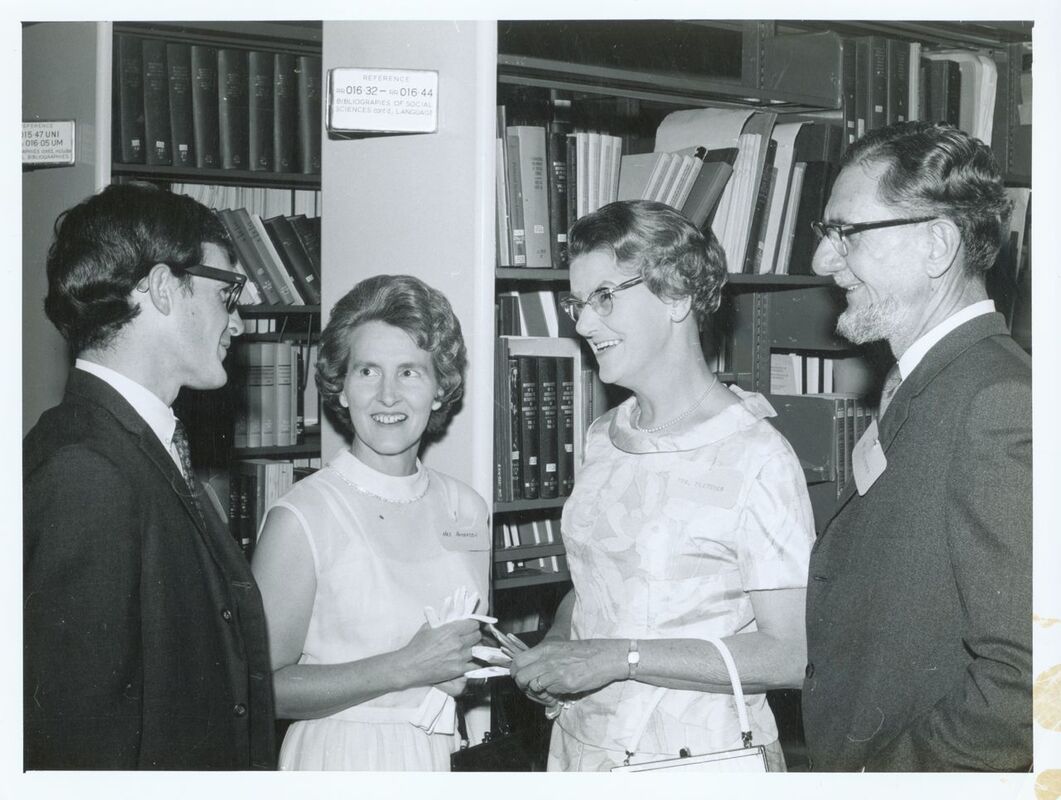

Betty Fletcher c. 1985 at the opening of a crate of new artefacts at the Antiquities Museum. Source: RD Milns Antiquities Museum Photographic Collection

Betty Fletcher c. 1985 at the opening of a crate of new artefacts at the Antiquities Museum. Source: RD Milns Antiquities Museum Photographic Collection Betty was educated at Somerville House in South Brisbane and won form prizes for English, French, Latin and Greek in the Junior Exam (Grade 10) in 1925. In 1927, during her Senior year, Betty was both School and Athletics Captain and won prizes for athletics and leadership. The same year, Betty was one of only 20 recipients of an Open Scholarship to the University of Queensland for 1928.

In 1967 the University of Queensland’s Alumni Association was formed and both Betty and Owen became active members. They were recognised for their contributions to the organisation with the granting of honorary life membership in 1988. Betty’s contributions were focused around her old discipline of Classics and Ancient History. She supported the Alumni Archaeological Scholarship, which provides funds for a student to travel and participate in an overseas excavation such as the University of Sydney’s Pella excavation, and in 1988 she became the inaugural patron of the new Friends of Antiquity group. Prior to this time, Betty had already established herself as a generous donor to the University’s Antiquities Museum. Donations of funds between 1980 and 1989 allowed the Museum to purchase a number of important artefacts:

- In 1980, a gold stater of Alexander the Great dating to 336–323 BC

- In 1984, an Urartian bronze fibula dating to 800–600 BC

- In 1986, a marble Attic Loutrophoros fragment, inscribed for “Phanodemos, the son of Paramonos, of the Deme of Aithalidai” on the occasion of the University of Queensland's 75th Anniversary; and

- In 1989, two Macedonian tetradrachms, one of Philip II, dating to 359–348 B, and the other of Philip V, dating to 221–179 BC, to mark her 80th birthday.

| “The Classics were always a very important part of Betty’s life, and she showed her concern for her favourite discipline by her constant and generous giving, both materially and of herself. Our fine Museum of Classical Antiquities owes much to the many benefactions of Betty over many years.” |

In 2019, the Friends of Antiquity established a second Betty Fletcher scholarship with a donation of $50,000, matched by the University, to support students studying Classics and Ancient History who are experiencing financial hardship. In 2020, the donation of $120,000 from the Alumni Friends of the University of Queensland secured the future of the Travelling Scholarship in perpetuity. A bronze portrait medallion of Betty by Dr Rhyl Hinwood, AM, mounted on Helidon freestone, is housed in the RD Milns Antiquities Museum and a copy was donated by Owen Fletcher to Somerville House. An inscription accompanying the medallion, composed by Prof. R.D. Milns, provides a fitting tribute:

Lover of Wisdom, Lover of Beauty, Lover of Humanity

Acknowledgements

References

- Fletcher, O., 1991. Our Life Together, Brisbane, Queensland: Boolarong Publications.

- Unknown. 1990. Rare Coins from Graduate Student. Brisbane, Queensland: University News.

- Clarke, E. 1985. Female Teachers in Queensland State Schools: A History 1860–1983, Brisbane, Queensland: Department of Education.

- Gregory, H. 2016. Fletcher, Owen Maynard (1908-1992). Canberra, ACT: Australian Dictionary of Biography.

Written by Dr Emilie Dotte-Sarout

University of Western Australia

These themes emerged during the research I have been undertaking for the previous five years as part of the team working on the ‘Collective Biography of Archaeology in the Pacific’ (CBAP ARC Laureate project led by Prof. Matthew Spriggs). As the very first consolidated and multilingual effort to investigate the historiography of archaeology in the region, highlighting the role of ‘hidden’ figures – namely indigenous collaborators and women engaged in the discipline – was part of our agenda. Yet, our experience clearly demonstrated the specific difficulties encountered in trying to ‘hear’ these hidden voices in the silences of the archives of Pacific archaeology. To overcome this, each of these topics needs to be examined on its own terms. For the women who were part of the development of archaeology in the Pacific to be included in the history of the discipline, explicit attention has to be given to the subject using a specific set of approaches and methods informed by gender studies and the feminist history of science, while integrating those used in the history of archaeology until now.

Women in the history of science

In particular, the first volume of Margaret Rossiter’s foundational Women Scientists in America (1982) not only demonstrated that many women had been active in American science since the 19th century despite not being represented in dominant historical narratives, but also that they developed specific strategies to overcome oppositional reactions and the segregated structuration of the scientific establishment. These observations hold true for the rest of the western world, with women scientists finding ways to advance knowledge and practice at least since antiquity (Watts 2007), including in the belatedly appearing disciplines of the social sciences (McDonald 2004; Carroy et al. 2005). Rossiter identified the gendered assumptions that tended to keep women out of science as a masculine field, writing that 19th century “women scientists were (…) caught between two almost exclusive stereotypes: as scientists they were atypical women; as women they were unusual scientists” (1982: xvi). This question has since been much examined by feminist historians of science (Watts 2007; Schiebinger 2014) and is certainly pertinent in regards to the first women who were interested in the emerging field of prehistory/archaeology in the Pacific: not only were they entering the masculine realm of science, but also those of fieldwork and the public sphere in exotic, mostly colonial spaces – not a woman’s place by any 19th century and early 20th century expectations. It must also be remembered that in most of the western world, sociocultural gendered norms were articulated with the legal subjugation of women, severely restricting their freedom and participation in public society until the 1960s in some of the European countries that played a role in the history of Pacific archaeology.

Finding the women in the history of Pacific archaeology

But I will not work alone on this project, and in addition to collaborative works with colleagues in Australia and elsewhere, postgraduate research projects are proposed within this DECRA. PhD candidate, Sylvie Brassard, has just started investigating the role, names, and legacies of the elusive group of women ‘volunteers’ working at the Musée de l’Homme during the emergence of the distinct school of French ‘archéologie océaniste’ in the mid-20th century. I am looking for interested postgraduate students to examine other topics, such as the particular dynamics that characterised the increasing engagement of women in New Zealand and Australian archaeology during the 20th century; the works and unusual careers of early women anthropologists sharing an interest in string figures; those who became specialists in material culture studies; and indigenous ‘folklorist’ experts in oral traditions linked to archaeological history. Finally, Dr India Dilkes-Hall is working with me to develop a database compiling the women’s scientific written outputs that we aim to make accessible online at the end of the project, offering a wide exposure to the Pacific Matildas’ legacies. We also want to use it as a tool to conduct citation rates analysis in the main and most enduring archaeology journals of the region to provide a comparable measure of research impact with their male colleagues and between themselves.

Together, we want to ensure that the ‘Matildas’ of Pacific archaeology are not left out of its history.

[1] Although Margarete Schurig also completed her museum-based doctoral dissertation Die Südseetöpferei (Pacific Pottery) in 1930 in Leipzig, which remained the foremost text on the subject for at least the next thirty years.

References

- Allen J. 1986. Evidence and Silence: Feminism and the Limits of History. In Pateman C. & Gross E. (eds) Feminist Challenges: Social and Political Theory. Allen & Unwin: 173–189.

- Carroy J., Edelman N., Ohayon A., Richard N. 2005. Les femmes dans les sciences de l’Homme (XIX-XXe siècles). Inspiratrices, collaboratrices ou créatrices. Seli Arslan.

- Claassen C. 1994. Women in Archaeology. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Cohen G. & Joukowsky M. 2004. Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists. University of Michigan Press. Diaz-Andreu M. & M.L.S. Sorensen. 1998. Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology. Routledge.

- Dotte-Sarout E., Maric T. and Molle G. Forthcoming. Aurora Natua and the motu Paeao site: Unlocking French Polynesia’s islands for Pacific archaeologists. In Jones T.H. Howes & Spriggs M. (eds) Uncovering Pacific Pasts: Histories of archaeology in Oceania. ANU Press, Acton (submitted August 2020).

- McDonald L. 2004. Women Founders of the Social Sciences. McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Rossiter M. 1982. Women scientists in America: Struggles and strategies to 1940. John Hopkins University Press.

- Rossiter M. 19993. The --Matthew-- Matilda Effect in Science, Social Studies of Science, 23 (2): 325-341. (NB: Matthew is a stikethrough in original reference)

- Schiebinger L. 2014. Women and Gender in Science and Technology. Routledge.

- Trouillot M-R. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press.

- Watts R. 2007. Women in Science. A Social and Cultural History. Routledge.

Eve Dray (1914-2005)

Part two of a two-part series on Eleanor Stewart and Eve Stewart and their contributions to Cypriot archaeology in Australia

Written by Dr Craig Barker

The University of Sydney

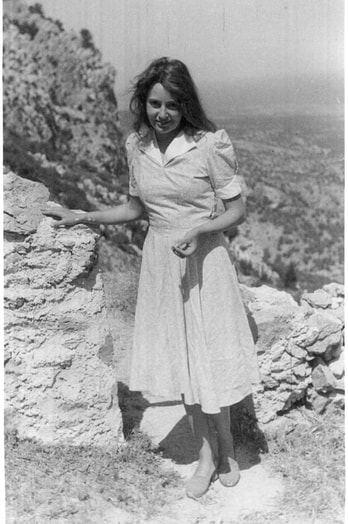

Eve Dray in Cyprus, 1947. Courtesy of Dorothy Eve Stewart Archives, University of New England (2013.149)

Eve Dray in Cyprus, 1947. Courtesy of Dorothy Eve Stewart Archives, University of New England (2013.149) Eve found that her work with the Cyprus Museum and her skills as an archaeological illustrator became highly valued on the island. One project she worked on was Vounous with the young Jim and Eleanor Stewart. Along with Joan and Sydney-born Margaret ‘Kim’ Collingridge, Eve was a participant in the excavations of tombs at Tsambres and Aphendrika (Dray and du Plat Taylor 1939). The adventures of the team were sensationally reported in the Australian media at the time: “Archaeologist mistaken for a spy” Sydney Morning Herald 15 December 1938.

In 1939 Tom Dray inherited a property and land at Tjikos in the north of Cyprus, assets that would be central to the rest of Eve’s life. The building came into his possession from William Scorseby Routledge, the widower of Katherine Routledge, the first female archaeologist to work in Polynesia. Eve would later assist in the tracking down of some of Routledge’s lost archaeological documents. The house at Tjikos over time became the base for much of Eve and Jim’s fieldwork on the island.

Eve and Jim Stewart at Mt Pleasant, Bathurst, 1953-54. Courtesy of Dorothy Eve Stewart Archives, University of New England (2013.149.1)

Eve and Jim Stewart at Mt Pleasant, Bathurst, 1953-54. Courtesy of Dorothy Eve Stewart Archives, University of New England (2013.149.1) The Stewarts conducted fieldwork campaigns in the 1950s in Cyprus on a series of Early and Middle Cypriot burials which were not on the ambitious scale that Jim had initially planned for his Australian fieldwork projects. By the time of the couple’s final excavations at Karmi in 1961, Jim was very ill, and he passed away in 1962.

Less successful was her aim to turn the property at Tjiklos into a centre for Australian archaeology in Cyprus, especially after the Turkish invasion of 1974. Attempts at establishing a foundation for the study of Cypriot archaeology at the University of New England were also unsuccessful. However, the money Eve raised from the sale of the Tjiklos house in 1986 was invested in the purchase of a building in Nicosia by the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute (CAARI) where today researchers and students of the archaeology of Cyprus can stay in the J.R. Stewart residence. Museums and universities across Australia are now homes to collections of Cypriot material from the Stewarts’ excavations.

Neither Eleanor nor Eve ever held an academic position, nor were their contributions to archaeology particularly celebrated during their lifetime beyond a general admiration for Eve’s determination to promote Jim’s legacy and complete his work. Thankfully, a greater acknowledgement of their respective contributions to Cypriot archaeology has finally begun.

Read The Mrs Stewarts. Part one - Eleanor Neal

References

- Dray, E. and J. du Plat Taylor, ‘Tsambres and Aphendrika: two Classical and Hellenistic cemeteries in Cyprus’, Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus 1937-39, 24–123

- Knapp, A.B., J.M. Webb and A. McCarthy (eds), J.R.B. Stewart: an archaeological legacy (SIMA CXXXIX: Uppsala 2013)

- Powell, J. Love’s Obsession: The Lives and Archaeology of Jim and Eve Stewart (Kent Town 2013)

- Stewart, E., ‘Eve Stewart on James Stewart’, in: A.B. Knapp, J.M. Webb and A. McCarthy (eds), J.R.B. Stewart: an archaeological legacy (SIMA CXXXIX: Uppsala 2013), xiii-xiv

- Webb, J.M., D. Frankel, K.O. Eriksson & J.B. Hennessy, The Bronze Age Cemeteries at Karmi Palealona and Lapatsa in Cyprus. Excavations by J.R.B. Stewart (SIMA 136: Sävedalen 2009).

Blog Subjects

All

About

Adele De Dombasle

AWAWS Project

Beryl Rawson

Betty Fletcher

Eleanor Stewart / Jacobs (nee Neal)

Eugenie Sellers Strong

Eve Stewart (nee Dray)

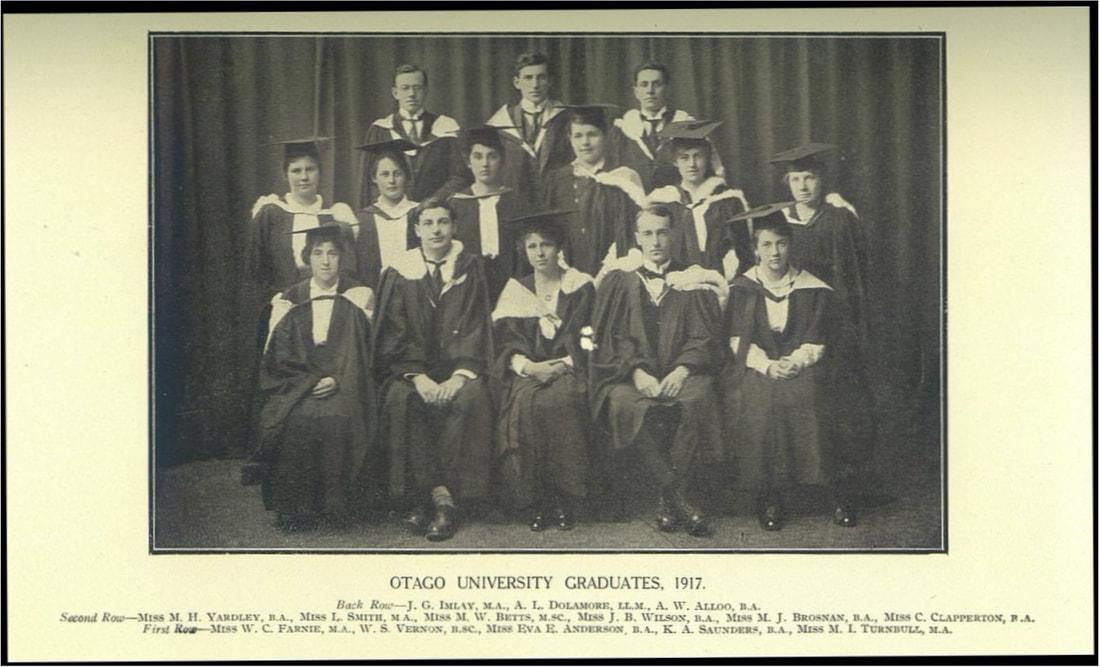

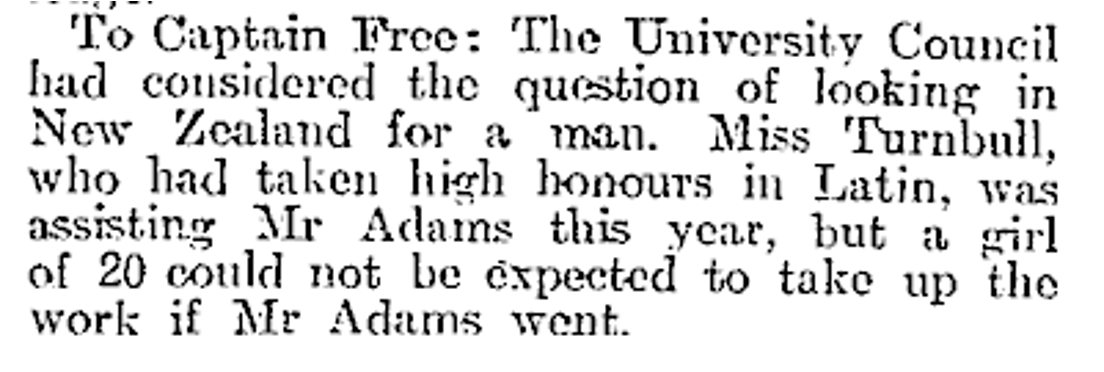

Isabel Turnbull

Jessie Webb

Judy Birmingham

Margaret Hubbard

Marguerite Johnson

Marion Steven

Marjorie Burnell (nee Smyth)

Olwen Tudor Jones

Pacific Matildas

Susanna Davies

Theme: Mrs

Theme: Museums

Theme: Research Methods

About the Blog

The contribution made by women to ancient world studies in Australia and New Zealand has often been neglected. Our blog aims to bring you new research and insights into some of these remarkable women.

Written by AWAWS members, these entries will hopefully be a starting point to discovering more about the diversity of people who have shaped our understanding of the ancient world.

Write for the Blog

We are currently seeking contributors to the blog. If you would like to write your own entry on any aspect of the history of women in ancient world studies, please get in touch with your idea and a draft outline of your entry via socawaws@gmail.com

Archives

January 2024

December 2022

August 2021

July 2021

May 2021

April 2021

February 2021

December 2020

November 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

December 2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed