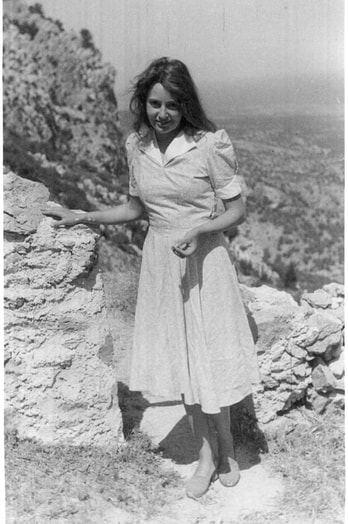

Eve Dray (1914-2005) |

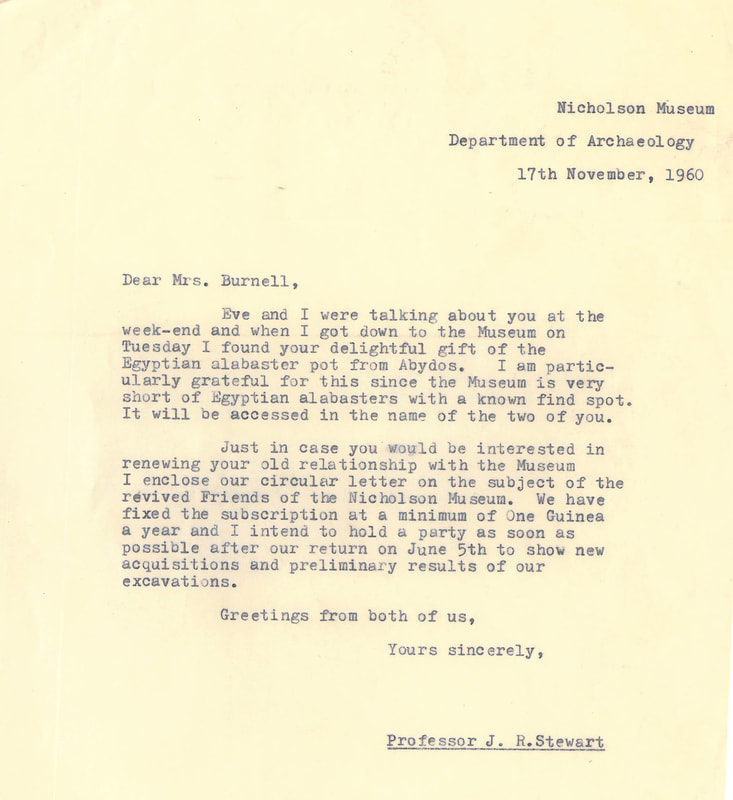

| “Relatively late in life in March 1935 Burnell became engaged to Marjorie Kane Smyth (1888–1974). She had worked as a nurse in Egypt and France during World War I, published a collection of her poetry, Poems, in London in 1919, and was also a painter, on one occasion exhibiting her works alongside other Australian artists in Paris at the Salon d’Automne in 1925” (Harting 2016, 85). |

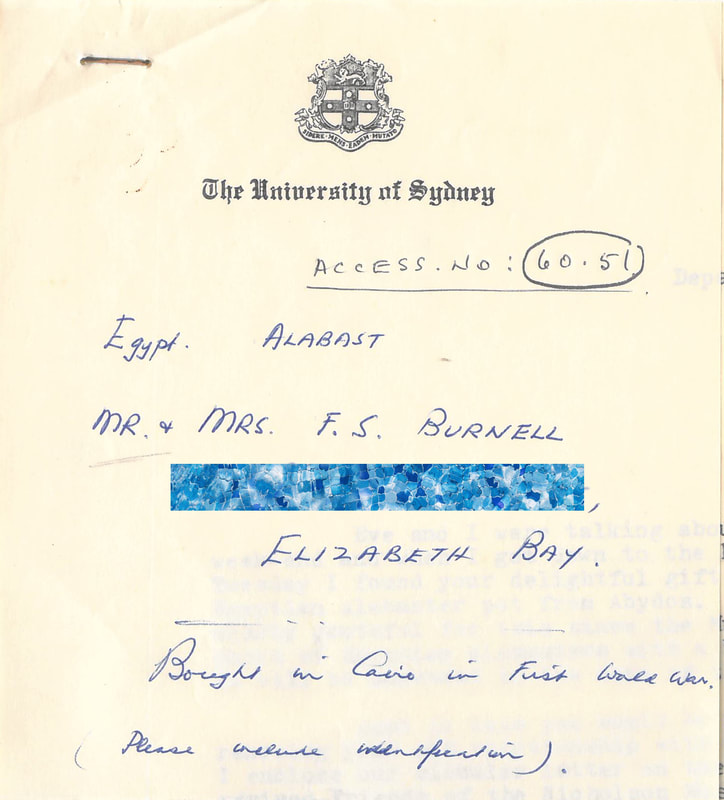

Marjorie Smyth’s service during WW1 places her squarely in Egypt, and we can be certain that she was the one who purchased the Abydos calcite jar, like many other service people who bought antiquities during their wartime postings. The fact that it was donated in both her married name and her husband’s, after he had passed, is not uncommon, and was followed up by Marjorie with a donation to the University of Sydney to endow a Classical Greek essay prize in Frederick’s honour in 1962 (Calendar 1963, 452).

The pitfalls of tracking married women in scholarship are varied and require active recognition of the many ways in which women can be easily written out, or in this case, ‘assumed out’ of history. The donation credit line for the Burnell’s Abydos jar has now been updated in the Nicholson Collection's databases to reflect the full names of both individuals, including an acknowledgement of Marjorie’s maiden name, and Marjorie has now been acknowledged as the collector of the item.

References

- Harting, Andrew. 2016. ‘Frederick Spencer ‘Fritz’ Burnell (1886-1958)’ in The Lysicrates Prize 2016: The People’s Choice. Sydney. 77-89.

- Newman, Vivien. 2016. Tumult and Tears: The story of the great war through the eyes and lves of its women poets. Barnsley, South York Shire.

- Calendar of the University of Sydney for the year 1963. Sydney 1962. accessed: http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/Calendar/1963/1963.pdf

Written by Dr Alina Kozlovski

Santa Barbara Museum of Art | The University of Sydney

Constance Phillott, 1890, 'Eugenie Sellers, Mrs Arthur Strong' - Image courtesty of The Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge.

Constance Phillott, 1890, 'Eugenie Sellers, Mrs Arthur Strong' - Image courtesty of The Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge. We have all seen old (and not so old) contexts which refer to a woman by her husband’s name with a Mrs attached. In the 1960s, Samantha from Bewitched became Mrs Darrin Stephens; in the 1990s Marge became Mrs Homer Simpson, and even today married women’s names sometimes get subsumed under their husband’s by banks and other institutions.

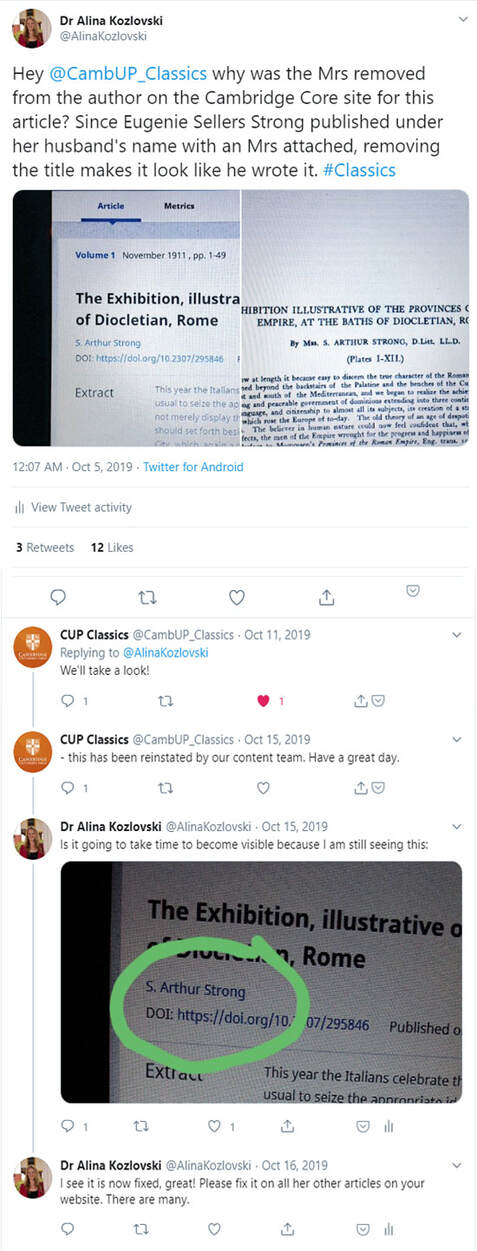

In the academic world, this older naming system meant that when women did publish their own research while they were married, it would be using this naming convention. A good example is Eugénie Sellers Strong who, among many other academic achievements, was Assistant Director of the British School at Rome (1909-25). In her many publications she is variously cited using her family name as Eugénie Sellers, her family and married names as Eugénie Sellers Strong, and her husband’s name as Mrs. S. Arthur Strong (This S is for Sandford which was Arthur Strong’s first name, initialised in his own publications). Having so many variations is confusing enough, but the convention of using a married name presents a big problem for not only citing, but also finding, the work of women in older scholarship.

Today, Mrs. is fast going out of style. In academic works, titles usually get omitted altogether in favour of using just a person’s surname to identify them. With modern standardised citation styles there is rarely a space to put a Mrs., Mr., or similar into a bibliography. Many authors, I’m sure usually with good intentions about modernising how women are referred to, see an older work and drop the Mrs. from their own bibliography when citing it. Unfortunately, with the Mrs. being the only marker that distinguishes the wife from the husband, the wife’s work then is referred to only using his name.

And so, Eugénie Sellers turns into Mrs. S. Arthur Strong upon marriage which then simply becomes S. Arthur Strong in a modern bibliography. In her case, this confusion is further complicated by the fact that her husband was also an archaeologist and published in his own right. Out of curiosity I googled the titles of some of her publications and, sure enough, in modern works they are sometimes found under his name rather than hers. We already know that a lot of work by women often goes uncredited, but in this case even when it was originally credited, it has become lost since.

Bibliographic conventions are not neutral in how they organise information and evolve as society’s standards change. As such, we have to be aware when we are dealing with an older system and double check that information is being carried across correctly. Who knows how many people’s contributions have been hidden behind someone else’s name.

Resources

- Suggestions on how to cite trans authors: https://medium.com/@MxComan/trans-citation-practices-a-quick-and-dirty-guideline-9f4168117115

- Suggestions on how to cite the knowledge of indigenous people and groups originally recorded by non-indigenous researchers: https://archivaldecolonist.com/2020/05/07/indigenous-referencing-prototype-non-indigenous-authored-works/

References

- Flower, Harriet. 1996, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture. Clarendon Press, New York.

- Warburg, Aby. 1999, The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: contributions to the cultural history of the European Renaissance. Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, Los Angeles.

Blog Subjects

All

About

Adele De Dombasle

AWAWS Project

Beryl Rawson

Betty Fletcher

Eleanor Stewart / Jacobs (nee Neal)

Eugenie Sellers Strong

Eve Stewart (nee Dray)

Isabel Turnbull

Jessie Webb

Judy Birmingham

Margaret Hubbard

Marguerite Johnson

Marion Steven

Marjorie Burnell (nee Smyth)

Olwen Tudor Jones

Pacific Matildas

Susanna Davies

Theme: Mrs

Theme: Museums

Theme: Research Methods

About the Blog

The contribution made by women to ancient world studies in Australia and New Zealand has often been neglected. Our blog aims to bring you new research and insights into some of these remarkable women.

Written by AWAWS members, these entries will hopefully be a starting point to discovering more about the diversity of people who have shaped our understanding of the ancient world.

Write for the Blog

We are currently seeking contributors to the blog. If you would like to write your own entry on any aspect of the history of women in ancient world studies, please get in touch with your idea and a draft outline of your entry via socawaws@gmail.com

Archives

January 2024

December 2022

August 2021

July 2021

May 2021

April 2021

February 2021

December 2020

November 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

December 2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed