Eleanor Neal (1911-2002) |

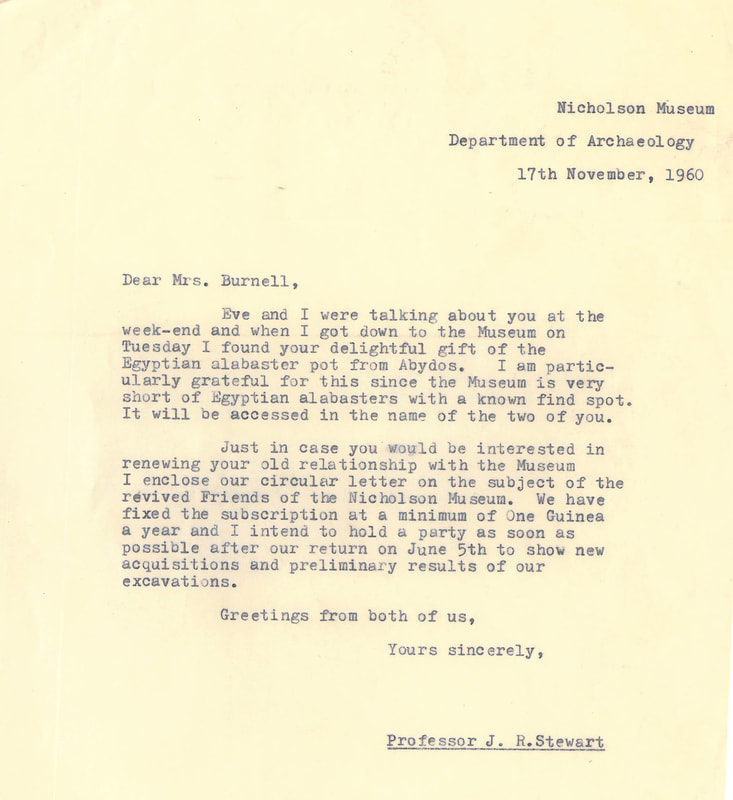

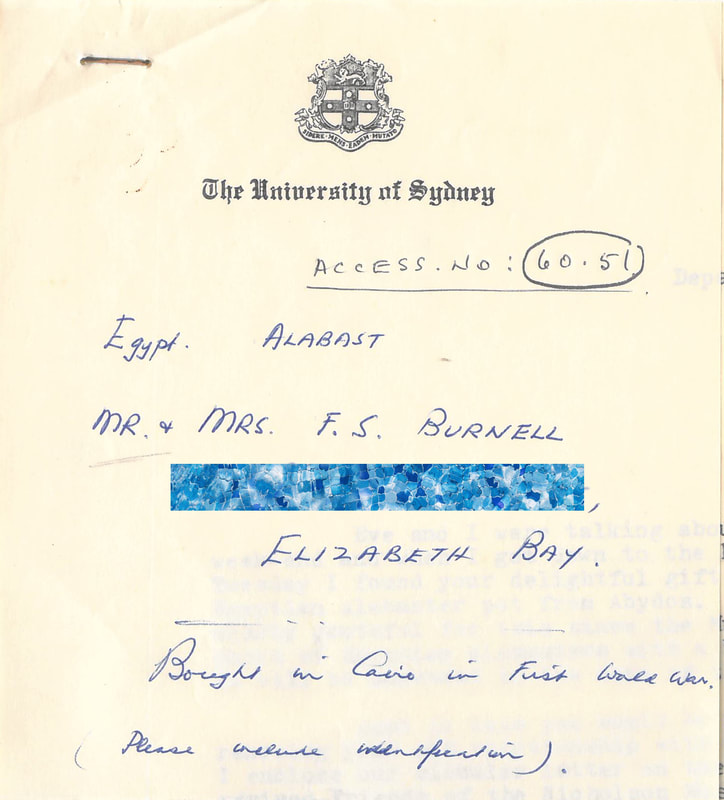

| “Relatively late in life in March 1935 Burnell became engaged to Marjorie Kane Smyth (1888–1974). She had worked as a nurse in Egypt and France during World War I, published a collection of her poetry, Poems, in London in 1919, and was also a painter, on one occasion exhibiting her works alongside other Australian artists in Paris at the Salon d’Automne in 1925” (Harting 2016, 85). |

Marjorie Smyth’s service during WW1 places her squarely in Egypt, and we can be certain that she was the one who purchased the Abydos calcite jar, like many other service people who bought antiquities during their wartime postings. The fact that it was donated in both her married name and her husband’s, after he had passed, is not uncommon, and was followed up by Marjorie with a donation to the University of Sydney to endow a Classical Greek essay prize in Frederick’s honour in 1962 (Calendar 1963, 452).

The pitfalls of tracking married women in scholarship are varied and require active recognition of the many ways in which women can be easily written out, or in this case, ‘assumed out’ of history. The donation credit line for the Burnell’s Abydos jar has now been updated in the Nicholson Collection's databases to reflect the full names of both individuals, including an acknowledgement of Marjorie’s maiden name, and Marjorie has now been acknowledged as the collector of the item.

References

- Harting, Andrew. 2016. ‘Frederick Spencer ‘Fritz’ Burnell (1886-1958)’ in The Lysicrates Prize 2016: The People’s Choice. Sydney. 77-89.

- Newman, Vivien. 2016. Tumult and Tears: The story of the great war through the eyes and lves of its women poets. Barnsley, South York Shire.

- Calendar of the University of Sydney for the year 1963. Sydney 1962. accessed: http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/Calendar/1963/1963.pdf

Written by Dr Alina Kozlovski

Santa Barbara Museum of Art | The University of Sydney

Constance Phillott, 1890, 'Eugenie Sellers, Mrs Arthur Strong' - Image courtesty of The Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge.

Constance Phillott, 1890, 'Eugenie Sellers, Mrs Arthur Strong' - Image courtesty of The Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge. We have all seen old (and not so old) contexts which refer to a woman by her husband’s name with a Mrs attached. In the 1960s, Samantha from Bewitched became Mrs Darrin Stephens; in the 1990s Marge became Mrs Homer Simpson, and even today married women’s names sometimes get subsumed under their husband’s by banks and other institutions.

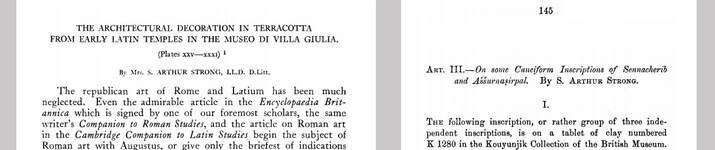

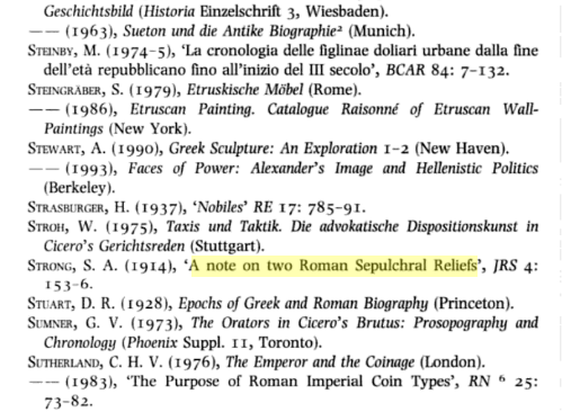

In the academic world, this older naming system meant that when women did publish their own research while they were married, it would be using this naming convention. A good example is Eugénie Sellers Strong who, among many other academic achievements, was Assistant Director of the British School at Rome (1909-25). In her many publications she is variously cited using her family name as Eugénie Sellers, her family and married names as Eugénie Sellers Strong, and her husband’s name as Mrs. S. Arthur Strong (This S is for Sandford which was Arthur Strong’s first name, initialised in his own publications). Having so many variations is confusing enough, but the convention of using a married name presents a big problem for not only citing, but also finding, the work of women in older scholarship.

Today, Mrs. is fast going out of style. In academic works, titles usually get omitted altogether in favour of using just a person’s surname to identify them. With modern standardised citation styles there is rarely a space to put a Mrs., Mr., or similar into a bibliography. Many authors, I’m sure usually with good intentions about modernising how women are referred to, see an older work and drop the Mrs. from their own bibliography when citing it. Unfortunately, with the Mrs. being the only marker that distinguishes the wife from the husband, the wife’s work then is referred to only using his name.

And so, Eugénie Sellers turns into Mrs. S. Arthur Strong upon marriage which then simply becomes S. Arthur Strong in a modern bibliography. In her case, this confusion is further complicated by the fact that her husband was also an archaeologist and published in his own right. Out of curiosity I googled the titles of some of her publications and, sure enough, in modern works they are sometimes found under his name rather than hers. We already know that a lot of work by women often goes uncredited, but in this case even when it was originally credited, it has become lost since.

Bibliographic conventions are not neutral in how they organise information and evolve as society’s standards change. As such, we have to be aware when we are dealing with an older system and double check that information is being carried across correctly. Who knows how many people’s contributions have been hidden behind someone else’s name.

Resources

- Suggestions on how to cite trans authors: https://medium.com/@MxComan/trans-citation-practices-a-quick-and-dirty-guideline-9f4168117115

- Suggestions on how to cite the knowledge of indigenous people and groups originally recorded by non-indigenous researchers: https://archivaldecolonist.com/2020/05/07/indigenous-referencing-prototype-non-indigenous-authored-works/

References

- Flower, Harriet. 1996, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture. Clarendon Press, New York.

- Warburg, Aby. 1999, The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: contributions to the cultural history of the European Renaissance. Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, Los Angeles.

(The Times, 13 May, 2011)

Written by Frances Muecke

The University of Sydney

Portrait of Margaret Hubbard. Courtesy of St Anne's College, Oxford University.

Portrait of Margaret Hubbard. Courtesy of St Anne's College, Oxford University. At school Margaret had a passion for Egyptology, but, as Adelaide University did not teach hieroglyphics, she studied Latin, Greek and English there, eventually tutoring in English. Her knowledge of English literature was deep and extensive and partly accounts for the special character of her work on Latin literature. At Oxford she read for the undergraduate degree (as was usual at that time for graduates from abroad), and afterwards had a period working for the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae in Munich, and studying manuscripts of Cicero’s agrarian speeches in Florence.

Margaret was as good a textual critic as anyone but the Cicero edition was not to be. In 1957 she became a Founding Fellow of a new Oxford college for women, St Anne’s, and their Mods don (classical languages and literature tutor), absorbed for the next nearly thirty years in the heavy duties of teaching, examining, and college and university governance, all of which she took very seriously. Research was done between 4 o’clock in the morning and breakfast. The long vacations provided the opportunity for camping trips in Greece and Italy.

Margaret’s way of teaching was to treat her students as her equals. If you worked really, really hard you might just be able to understand. Then it was exciting, but it was easy, despite her kindness, to feel intimidated by her force of intellect and superb memory. She was a generous teacher. Some graduate students I knew, dissatisfied with their designated supervisors, found their way to her, completed successfully and became devoted friends. Such friendships were consolidated around her dining table with excellent food and wine.

In keeping with the prevailing expectations of her time — the one book that was the summation of a lifetime’s research — and her own high standards (she prized truly new insights) Margaret did not publish much at first. What must have been many years of early-morning labour came to fruition in 1970 with the publication of the famous 440-page Oxford commentary on Horace Odes Book 1, written jointly with R. G. M. Nisbet. One quote sums up the enthusiastic reactions of reviewers: ‘no commentary of equal stature has appeared in our days.’ (Sullivan, 1971, 116) To students of my era it came as a revelation: traditional commentaries could be cutting edge. The second volume followed in 1978.

But where Margaret can be seen most clearly is in her ‘own’ book, Propertius (London, 1974) — trenchant, original, erudite and focussed on questions that matter. It is still a landmark, even if was overtaken by the ‘New Latinist’ innovations of the next generation. (She examined the D. Phil. thesis of one of the most famous New Latinists, Don Fowler.) Around the same time she published a carefully considered and highly-regarded translation of Aristotle’s Poetics (1972), and her final project was a history of the reception of that work, abandoned after her retirement, which she spent happily with her partner Gwynneth Matthews, in her favourite pursuits: wide reading, cooking, gardening, travel and cross-words.

References

- Hubbard, Margaret E. 1972. “Aristotle: Poetics,” in D. A. Russell and M. Winterbottom (ed.), Ancient Literary Criticism, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Sullivan, Frances, A. 1971. “A Commentary on Horace: Odes, Book 1. R. G. M. Nisbet, Margaret Hubbard," Classical Philology vol. 66, no. 2, pp.116-117.

- "Girl wins Tennyson Medal" The Adelaide Advertiser (13 January 1940): 22. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/35660170

- "Remarkable Scholarship of S.A. Graduate" The Adelaide Advertiser, (18 September 1953): 3 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/48929607

- "Margaret Hubbard" The Times (13 May 2011) https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/margaret-hubbard-kpvkmc8gww0

Written by Candace Richards

The University of Sydney

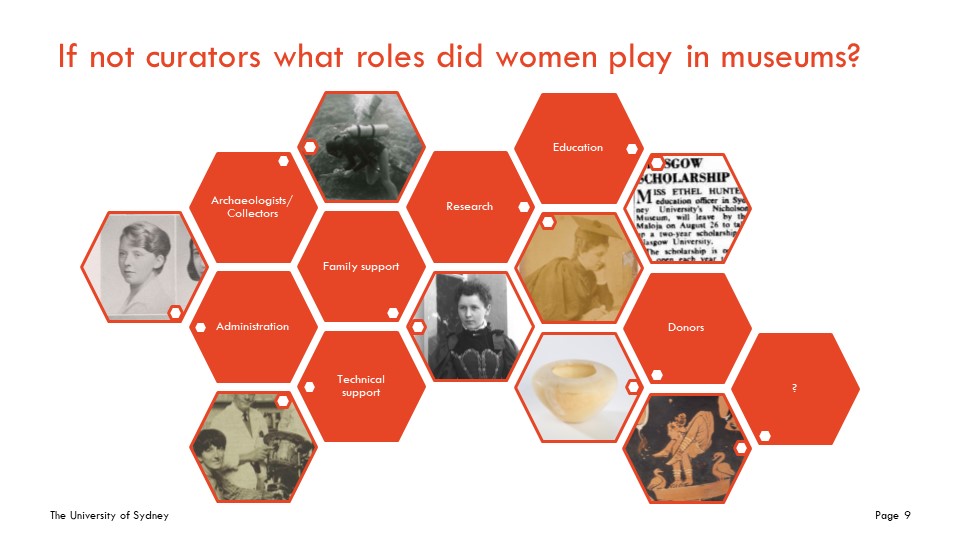

Archival research at the Nicholson has revealed that women’s contributions come in many forms including administrative and technical support often undertaken behind the scenes for the improvement of the collections; research and publication of the collections; education and public outreach; collecting activities, often as part of archaeological research on behalf of the museum or financing collecting practices; donors to the collection; and finally, as family support when women are often active in the research or collecting process and then if outliving their partner assume responsibility for the management of collections and posthumous legacies. The teasing out of the individual stories and collective roles women played is part of my long-term research project ‘The Hidden Women of the Nicholson Museum.’ It is hoped that in addition to highlighting the many accomplishments and contributions women have made throughout the history of the Nicholson, we can examine how we construct our own histories, and offer new approaches to constructing historically accurate and inclusive institutional narratives.

Written by Natalie Looyer

University of Canterbury, NZ

Marion Steven and James Logie attending a university ball, c.1950. Copyright Steven Family.

Marion Steven and James Logie attending a university ball, c.1950. Copyright Steven Family. Those in the Department who had known Marion spoke about her with warmth and joviality. When the opportunity for an oral history project on Marion’s life was suggested, I jumped at the chance and set about interviewing family, friends, past students and colleagues of Marion. The project took me up and down New Zealand and as far as Sydney and Adelaide where I followed the threads of Marion’s network. Throughout these interviews – twelve in total – I learned about Marion’s impressive career as a scholar, a collector and a teacher. Through the memories of those closest to her I came to understand the extraordinary legacy that she left behind, not only in her remarkable collection of antiquities, but also in the influence that she had on the lives of great Classics scholars whom she nurtured.

Marion began her academic career in Medicine, excelling at university and receiving a medical scholarship to a London Hospital. But she was rejected upon arrival, as her application had not made it clear that she was a woman. Marion then turned to Classics – perhaps what she had wished to study all along. She soon began teaching at the University, where her compassion for students earned her their respect. She valued the traditional learning of Latin and Greek, but she also valued material culture as a way of understanding life in the ancient world, which inspired her to begin collecting antiquities for her teaching.

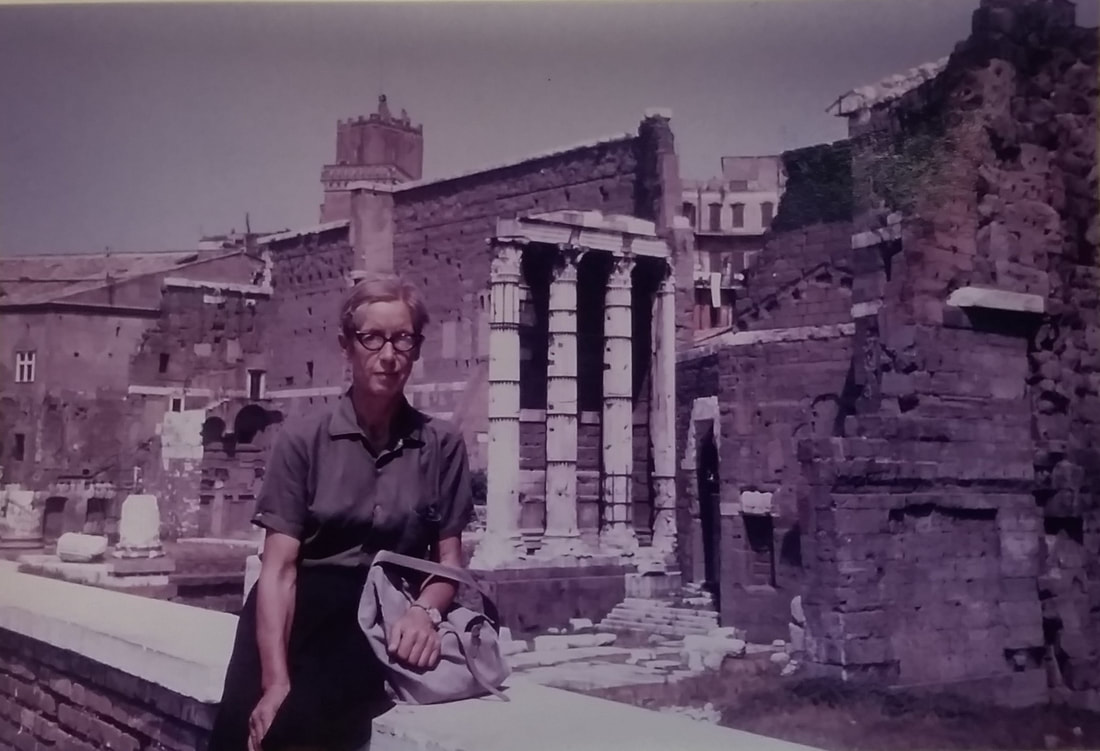

Marion Steven before the Forum of Augustus in Rome, 1970. Copyright University of Canterbury.

Marion Steven before the Forum of Augustus in Rome, 1970. Copyright University of Canterbury. Marion developed relationships with prestigious scholars such as Dale Trendall and John Beazley, which put the Logie Collection on the global map. But Marion’s most cherished relationships were to those in her close community. Her family and students remembered her as an advocate for young people, especially young women. She took her students seriously. She was generous with her time, hosting many of her students at her own house gatherings. And she was generous with her resources, gifting her collection of antiquities to the University for future generations of Classics students.

Marion continued to enjoy visits from her past students well into her retirement. One of my favourite comments in an interview comes from Professor Edwin Judge of Macquarie University, a past student of Marion. When speaking about his return visits to his hometown in Christchurch, he said, “Marion, we assumed, would always be there. And nothing could possibly be wrong in Christchurch with Marion there.”

Edwin’s comment seemed particularly pertinent in the context of the Christchurch earthquakes, which, eleven years after Marion’s passing, caused extensive damage to the Logie Collection. But Marion’s attitude – that if something fell out of her bike and broke, it could just be put back together again – stood the test of time. After an extensive rehabilitation project in 2014, the Logie Collection was fully conserved and is now on public display at the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities in Central Christchurch. Marion’s legacy lives on in her collection, but as my interviewees pre-eminently remembered Marion’s warmth and generosity over her material contributions, I came to realise that perhaps her greatest gift was the way in which she fostered her community and those around her.

Olwen Tudor Jones (1916-2001), was an archaeologist, finds manager, archivist, teacher and mentor. She was Research Assistant to the AAIA’s founding director, the late Professor Alexander Cambitolgou. She was an amazing woman who mentored many budding archaeologists over the course of her career.

Olwen was one of the main editors on the AAIA publications Zagora 2 and Torone 1. The interview you see here was recorded during the 1984 field season at Torone, near the southern end of the Sithonia peninsula of the Chalkidike.

In the background of the video, the young man you can see working so diligently is now the AAIA’s Acting Director, Dr Stavros Paspalas. On watching the archival footage this week Dr Paspalas commented:

“Olwen Tudor Jones was an inspiration; a warm and indomitable person who was always as eager to impart her experiences and knowledge to others as she was to learn from them. And, indeed, she had a wealth of experiences to share. Olwen played a major role in the process by which I was fortunate enough to become an archaeologist. The months I spent with her in the “pot shed” at Torone expanded my interest in how ceramics can be studied so that we may learn about past societies and confirmed my desire to pursue archaeology seriously. More importantly, though, I learnt from Olwen the value of following one’s interests wherever they may take you. I owe a great deal to Olwen.”

– Dr Stavros PaspalasHer legacy continues to provide opportunities for archaeology students at the University of Sydney. A scholarship in her name is funded by her family, friends and former mentees, who wished to continue her commitment to supporting young students, intellectually, emotionally and financially.

The Olwen Tudor Jones Scholarship is administered by the Society of Mediterranean Archaeology. The scholarship is offered on an annual basis, and the 2020 application round will open soon. For more details, please visit the OTJ Scholarship page.

Her legacy indeed continues and we are proud to remember her on International Women’s Day, 2020.

Natalie Looyer, from the University of Canterbury, was first to present her paper ‘The Academic Legacy of Miss Marion Steven.’ This was the culmination of Natalie’s wide ranging oral history project on the legacy of the woman who not only founded the Logie Collection, but whose legacy can be measured by the success of her students and who is remembered as a remarkable teacher who shaped the lives of generations of classicists.

Throughout the conference, AWAWS was proud to also support an anti-bullying workshop, drinks for members and hold a special meeting in which it launched its new mentoring program. Each of these activities was supported generously by the ASCS which co-sponsored events and facilitated our participation. A special thanks to Dr Daniel Osland, conference convenor, and AWAWS Treasurer, Gwynaeth McIntyre, for their wonderful work organising the conference and for their support for the AWAWS events.

Abstracts from each our of presenters are available in the ASCS41 conference program - https://www.otago.ac.nz/classics/ascs-2020.htm

Alia Astra: A History of Australasian Women in Ancient World Studies was organized by Rachel Yuen-Collingridge and Lea Beness on behalf of AWAWS in an attempt to start charting, compiling and publicising that history. This event was held at Macquarie University on the 26th April 2019 and consisted of a full day workshop followed by a panel discussion open to the public.

The workshop aimed to consolidate efforts to collect and work up data towards a history of Australasian women in Ancient World Studies by bringing together scholars who have worked on, or are undertaking, research on women in the field in Australia and New Zealand. Scholars working on the living or past history of women in the discipline came together to share findings and mapped out a special journal issue dedicated to a history of women in the discipline in the next two years, as well as a five-year strategy for the ongoing effort to collect, archive, and disseminate information on women in the discipline for the future.

The day culminated in a panel discussion, featuring Natalie Looyer, Mary Spongberg and Michelle Arrow and chaired by AWAWS President Lea Beness, which discussed the issues involved in developing a history of women in the field.

Registration for the day included on online survey. Our survey is still available here. If you could not attend but have worked in this area, please still register or email to let us at the AWAWS email address listed above to let us know about your efforts and how you might like to be incolved in the future.

Our blog aims to bring you new research and insights into some of these remarkable women. Written by AWAWS members, these entries will hopefully be a starting point to discovering more about the diversity of people who have shaped our understanding of the ancient world.

Get involved

We are currently seeking contributors to the blog. If you would like to write your own entry on any aspect of the history of women in ancient world studies, please get in touch with your idea and a draft outline of your entry via [email protected]

Preliminary work is underway for a special journal issue on the History of Women in Ancient World Studies. But in order to do this, we need your help. We are gathering material on women in the discipline who made a significant contribution to the field and the life of classics and ancient world studies in Australia and New Zealand. If have any bibliography, photographs, letters, course outlines, articles, stories, anecdotes or would be interested in contributing to future scholarly publications please contact Lea Beness, AWAWS President [email protected]. You can read more about our Alia Astra workshop and event here.

Blog Subjects

All

About

Adele De Dombasle

AWAWS Project

Beryl Rawson

Betty Fletcher

Eleanor Stewart / Jacobs (nee Neal)

Eugenie Sellers Strong

Eve Stewart (nee Dray)

Isabel Turnbull

Jessie Webb

Judy Birmingham

Margaret Hubbard

Marguerite Johnson

Marion Steven

Marjorie Burnell (nee Smyth)

Olwen Tudor Jones

Pacific Matildas

Susanna Davies

Theme: Mrs

Theme: Museums

Theme: Research Methods

About the Blog

The contribution made by women to ancient world studies in Australia and New Zealand has often been neglected. Our blog aims to bring you new research and insights into some of these remarkable women.

Written by AWAWS members, these entries will hopefully be a starting point to discovering more about the diversity of people who have shaped our understanding of the ancient world.

Write for the Blog

We are currently seeking contributors to the blog. If you would like to write your own entry on any aspect of the history of women in ancient world studies, please get in touch with your idea and a draft outline of your entry via [email protected]

Archives

January 2024

December 2022

August 2021

July 2021

May 2021

April 2021

February 2021

December 2020

November 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

December 2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed